Drop (liquid)

A drop or droplet is a small column of liquid, bounded completely or almost completely by free surfaces. A drop may form when liquid accumulates at the lower end of a tube or other surface boundary, producing a hanging drop called a pendant drop. Drops may also be formed by the condensation of a vapor or by atomization of a larger mass of liquid.

Contents |

Surface tension

Liquid forms drops because the liquid exhibits surface tension.

A simple way to form a drop is to allow liquid to flow slowly from the lower end of a vertical tube of small diameter. The surface tension of the liquid causes the liquid to hang from the tube, forming a pendant. When the drop exceeds a certain size it is no longer stable and detaches itself. The falling liquid is also a drop held together by surface tension.

Pendant drop test

In the pendant drop test, a drop of liquid is suspended from the end of a tube by surface tension. The force due to surface tension is proportional to the length of the boundary between the liquid and the tube, with the proportionality constant usually denoted  .[1] Since the length of this boundary is the circumference of the tube, the force due to surface tension is given by

.[1] Since the length of this boundary is the circumference of the tube, the force due to surface tension is given by

where d is the tube diameter.

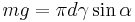

The mass m of the drop hanging from the end of the tube can be found by equating the force due to gravity ( ) with the component of the surface tension in the vertical direction (

) with the component of the surface tension in the vertical direction ( ) giving the formula

) giving the formula

where α is the angle of contact with the tube, and g is the acceleration due to gravity.

The limit of this formula, as α goes to 90°, gives the maximum weight of a pendant drop for a liquid with a given surface tension,  .

.

This relationship is the basis of a convenient method of measuring surface tension, commonly used in the petroleum industry. More sophisticated methods are available when the surface tension is unknown that consider the developing shape of the pendant as the drop grows.[2] [3]

Droplet

The term droplet is a diminutive form of 'drop' - and as a guide is typically used for liquid particles of less than 500 µm diameter. In spray application, droplets are usually described by their perceived size (i.e., diameter) whereas the dose (or number of infective particles in the case of biopesticides) is a function of their volume. This increases by a cubic function relative to diameter; thus a 50 µm droplet represents a dose in 65 pl and a 500 µm drop represents a dose in 65 nanolitres.

Optics

Due to the different refractive index of water and air, refraction and reflection occur on the surfaces of raindrops, leading to rainbow formation.

Sound

The major source of sound when a droplet hits a liquid surface is the resonance of excited bubbles trapped underwater. These oscillating bubbles are responsible for most liquid sounds, such as running water or splashes, as they actually consist of many drop-liquid collisions.[4][5]

Shape

The classic shape associated with a drop (with a pointy end in its upper side) comes from the observation of a droplet clinging to a surface. The shape of a drop falling through a gas is actually more or less spherical. Larger drops tend to be flatter on the bottom part due to the pressure of the gas they move through.[6]

Size

Scientists traditionally thought that the variation in the size of raindrops was due to collisions on the way down to the ground. In 2009 French researchers succeeded in showing that the distribution of sizes is due to the drops' interaction with air, which deforms larger drops and causes them to fragment into smaller drops, effectively limiting the largest raindrops to about 6 mm diameter.[7]

Gallery

See also

References

- ^ Cutnell, John D.; Kenneth W. Johnson (2006). Essentials of Physics. Wiley Publishing.

- ^ Roger P. Woodward, Ph.D. (PDF). Surface Tension Measurements Using the Drop Shape Method. First Ten Angstroms. http://www.firsttenangstroms.com/pdfdocs/STPaper.pdf. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- ^ F.K.Hansen; G. Rodsrun (1991). "Surface tension by pendant drop. A fast standard instrument using computer image analysis". Colloid and Interface Science 141: 1–12. doi:10.1016/0021-9797(91)90296-K.

- ^ Prosperetti, Andrea; Oguz, Hasan N. (1993). "The impact of drops on liquid surfaces and the underwater noise of rain" (PDF). Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 25: 577–602. Bibcode 1993AnRFM..25..577P. doi:10.1146/annurev.fl.25.010193.003045. http://arjournals.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.fl.25.010193.003045. Retrieved 2006-12-09.

- ^ Rankin, Ryan C. (June 2005). "Bubble Resonance". The Physics of Bubbles, Antibubbles, and all That. http://ffden-2.phys.uaf.edu/311_fall2004.web.dir/Ryan_Rankin/bubble%20resonance.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-09.

- ^ "Water Drop Shape". http://www.newton.dep.anl.gov/askasci/gen01/gen01429.htm. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ^ Emmanuel Villermaux, Benjamin Bossa (September 2009). "Single-drop fragmentation distribution of raindrops.". Nature Physics 5 (9): 697–702. Bibcode 2009NatPh...5..697V. doi:10.1038/NPHYS1340. https://www.irphe.fr/~fragmix/publis/VB2009.pdf. Lay summary.

External links

- Liquid Sculpture - pictures of drops

- Liquid Art - Galleries of fine art droplet photography

- Tvw Gallery of Drops - pictures of drops

- (Greatly varying) calculation of water waste from dripping tap: [1], [2]

- Liquid Photography - Sudhakar